Inside a deep Xiongnu grave hidden in the thickly wooded Sudzuktè pass, on the bottom of the burial chamber, archaeologists, participants of the Russian-Mongolian expedition, found what they had long been searching for: a layer of clay revealing the outline of textile relics. The fragments of the textile found were parts of a carpet composed of several cloths of dark-red woolen fabric. The time-worn cloth found on the floor covered with blue clay of the Xiongnu burial chamber and brought back to life by restorers has a long and complicated story. It was made someplace in Syria or Palestine, embroidered, probably, in north-western India and found in Mongolia.

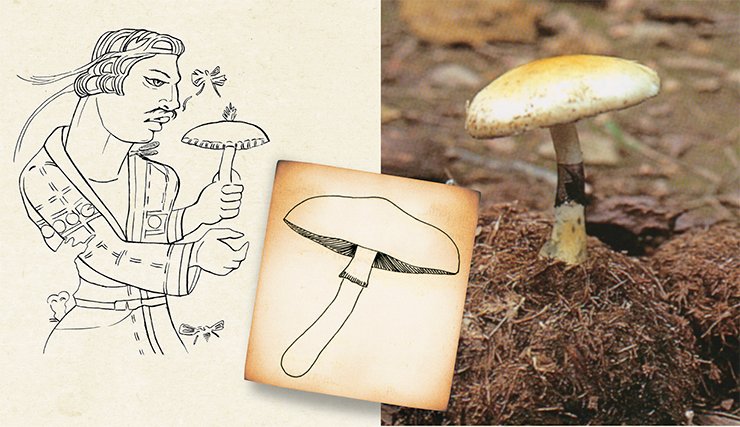

Finding it two thousand years later is a pure chance; its amazingly good condition is almost a miracle. How it made its way to the grave of a person it was not meant for will long, if not forever, remain a mystery. Of greatest surprise though was the unique embroidery made from wool. Its pattern was the ancient Zoroastrian ceremony, of which the principal personage was …a mushroom. In the center of the composition to the left of the altar is the king (priest), who is holding a mushroom over the fire. The «divine mushroom» embroidered on the carpet resembles well-known psychoactive species Psilocybe cubensis.

The weight of evidence suggests that soma, the ancient ritual drink, has been prepared from the mushrooms of family Strophariaceae which contain the unique nervous system stimulator psilocybin

Diggings of 31 Xiongnu tumuli (dated from the late 1st c. B.C. to the early 1st c. AD) of the Noin-Ula burial ground (Mongolia) carried out in 2009 by an expedition of the Institute of Archaeography and Ethnography, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (SB RAS), have discovered embroidered woolen textiles preserved by a miracle. Their complete restoration is a long way to go; however, the first fragments restored have revealed exceptional information

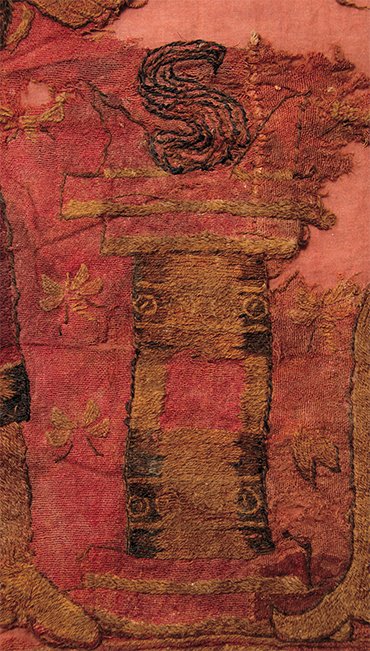

On the altar the flame burns – two tongues on the sides and an S-shaped sign in the middle. The flame of king’s fireplace mounted on the altar is a symbol of royal grandeur

This was the third find to date; all of them were made in the well-known Xiongnu burial ground of Noin-Ula: the first fragments of a unique textile were found here as early as in the 1920s by the expedition of the eminent traveler and scholar P. K. Kozlov. Like many other things, the precious fabrics happened to be in the graves of rich nomads because of the trade along the Silk Road. Xiongnu did not participate in the trade deals but they controlled a long stretch of this perennial spring of foreign goods.

Basing on the first find, the researchers believed that the textile from the Xiongnu burial ground was made in Bactria (Pugachenkova, 1966). However, the finds made in 2006 and 2009 do not allow identifying this textile so unambiguously. Of greatest surprise though was the find made in 2009, or, to be more exact, the unusual pattern involving people and animals embroidered on the textile.

The fragments of the textile found were parts of a carpet composed of several cloths of dark-red woolen fabric. The fabric itself mast have been meant for mantles. A sign of this is the narrow maroon woven stripes with “pockets.” These important ornamental details are known not only from the numerous finds of real textiles in Dura-Europos, Syria, in Palmira and in the Palestinian Cave of Letters, but also from frescos, paintings on Egyptian sarcophagi, and early Christian mosaics (Yadin, 1963).

Similarly to the known mantle textile, the woven stripes of the Xiongnu find do not go from one edge to the other but begin and end within a single cloth. Their cut bits were sewn together without taking into account the location of woven stripes: the ornamental element, so important for making mantles, this time proved to be unnoticed.

The embroidered fabric filled the narrow space between the chamber’s wooden walls and the coffin, which was placed in the middle on another, not embroidered textile. As a matter of fact, the embroidered carpet was laid along the corridor used for the burial ceremony. On top of the fabric was a thick layer of blue clay brought on purpose, which, according to the Chinese tradition was used to make the chamber waterproof. This clay cover made the restorers’ work very hard but preserved the textile.

Beside the altar flame

Men in Iranian dress, equipped with daggers and long swords, approach the fire

The restorers’ hands have revealed the following embroidered plot: a procession to the altar. The altar itself – support for the fire – is a column with a base consisting of two steps and a two-step top turned upside-down. The column shows depictions of circles with a dot in the center – the widespread ancient symbol of fire and the Sun. In the Achaemenid time, similar altars were a novelty introduced by Persians, who proclaimed their adherence to the Zoroastrian belief. “The flame of the king’s fireplace, going upwards in this way, became a symbol of their grandeur.” (Boyce, 1988, p. 75—76).

The altar is aglow with the fire. These Zoroastrian fires had a martial spirit: those who prayed to them were warriors fighting on the side of good creatures against gloom and cold, evil and ignorance.

…Men are approaching the fire. They are armed with daggers attached to the right thigh and long swords with a ring or round pommel and long grip appended to the belt on the left. The warriors are wearing Iranian garments – red trousers, narrow or loose, and closely fitting jackets, wrapped on the left, or longer kaftans. The dress is girdled with a buckled belt and lined with fur.

The warriors’ black voluminous tresses, set in rows and cut at the length of ear lobes, are sometimes strapped across the forehead with a narrow ribbon with fluttering ends. Their looks are conspicuous: expressive profiles of their broad round faces with big eyes, soft chins, pudgy lips and big, slightly aquiline noses. The faces are shaved, though many have a black narrow moustache above the upper lip.

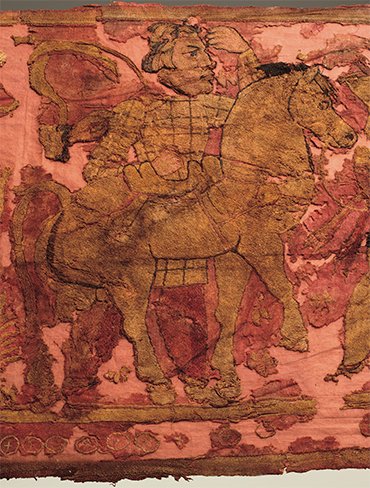

A dismounted rider wearing an armor-clad long jacket with something like a scarf or a cloak fluttering behind his back attracts special attention. His beardless face is stern. The left hand is raised to the forehead in a gesture of adoration common as early as during the Achaemenids as a sign of worshipping a deity. The rider’s horse is held by the bridle by an armed man in a short jacket with something like a scrip on his back from which something like a mushroom is peeking out.

The manner in which the warrior with a horse is depicted copies in minute detail the images on the heads of the coins minted by Indo-Scythian (Saka) kings: Azes I, Aziles и Azis II, who governed north-western India approximately from 57 BC, as well as by their successor Gondofar, the first Indo-Parthian ruler of West and East Punjab (from 20 AD to 46 AD).

A dismounted rider wearing an armor-clad jacket raised his left hand to the forehead in the traditional Zoroastrian gesture – the sing of worshipping a deity (left). Drawing of the carpet by Ye. Shumakova. The depictions of embroidered riders on the carpet and rulers on the heads of Indo-Scythian coins have a great deal in common. On the right are the coins of Azes II, on the left is their drawing. From: (Musee National des Arts Asiatiques-Guimet – l’Asie des steppes d’Alexandre le Grand à Gengis Khan, 2000)

On these coins we can see similar stocky round horses with long tails and strapped docks, cut in a particular manner: a hogged plait at the tail head. Like the embroidered horse, their breast collars are decorated with plates.

The saddle with four horn-shaped supports is identical to the reconstruction made on the basis of Roman archaeological data (Connoli, 2001) with the only difference: instead of leather laces hanging down from under the saddle, there are two clawed paws of a predator’s hide that was used as a horsecloth. These saddles are believed to have appeared by the beginning of the Parthian period and were widely spread with the Parthian cavalry; they were also known to the Sarmatians. Similarly to the embroidered warrior, the riders on the coins are wearing tight waist jackets sewn around with big rectangular plates – such armor was known to the Sakai and Parthians.

These similarities are an important argument in favor of the hypothesis that the carpet shows Indo-Scythians or Indo-Parthians.

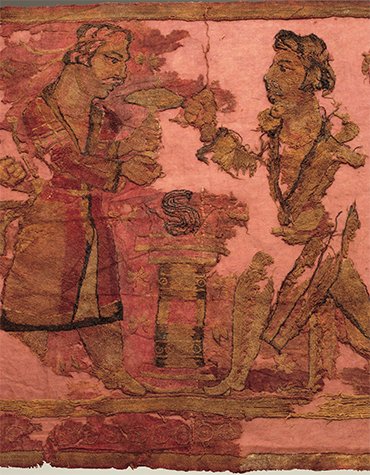

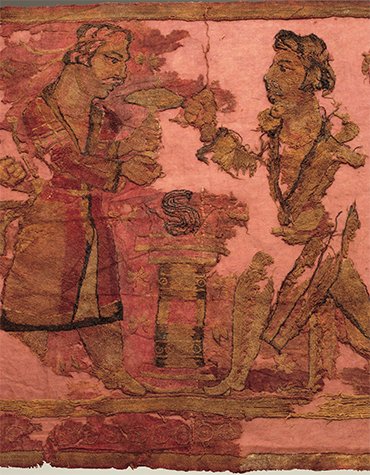

Divine mushroom

To the left of the altar is the king (priest), who is holding a mushroom over the fire. Opposite him is a warrior in a jacket with a “tail” and a belted quiver The embroidered plot develops further… We can see people standing absorbedly around the altar fire. The most prominent figure among them is the man on the left – probably, the king himself or a priest – dressed in a smart long embroidered kaftan gaping open at the bottom. He has a rarely expressive face, and his intent look is focused on the mushroom he is holding in both hands.

A priest with the Divine Mushroom in his hand... The question of what plant was used to prepare soma, or haoma – the drink of gods ancient Indians and Iranians imbibed has been debated for over a hundred years. Up to now, the plant whose sap was a permanent participant of the rituals, an offering to gods made by ancient Indians and Iranians, has not been identified. The hypotheses are plenty: from ephedra, cannabis, and opium poppy to oriental lotus (e.g., Abdullaev, 2009; McDonald, 2004; et al.). All researchers agree that ancient Indians and Iranians used for cult purposes a drink containing a psychoactive substance – it is only debatable what it was exactly and how it affected the people’s consciousness.

A scene from the Eleusinian Mysteries: Persephone taking a mushroom from Demeter. C. 4th c. BC

A dismounted rider wearing an armor-clad jacket raised his left hand to the forehead in the traditional Zoroastrian gesture – the sing of worshipping a deity (left). Drawing of the carpet by Ye. Shumakova. The depictions of embroidered riders on the carpet and rulers on the heads of Indo-Scythian coins have a great deal in common. On the right are the coins of Azes II, on the left is their drawing. From: (Musee National des Arts Asiatiques-Guimet – l’Asie des steppes d’Alexandre le Grand à Gengis Khan, 2000)

On these coins we can see similar stocky round horses with long tails and strapped docks, cut in a particular manner: a hogged plait at the tail head. Like the embroidered horse, their breast collars are decorated with plates.

The saddle with four horn-shaped supports is identical to the reconstruction made on the basis of Roman archaeological data (Connoli, 2001) with the only difference: instead of leather laces hanging down from under the saddle, there are two clawed paws of a predator’s hide that was used as a horsecloth. These saddles are believed to have appeared by the beginning of the Parthian period and were widely spread with the Parthian cavalry; they were also known to the Sarmatians. Similarly to the embroidered warrior, the riders on the coins are wearing tight waist jackets sewn around with big rectangular plates – such armor was known to the Sakai and Parthians.

These similarities are an important argument in favor of the hypothesis that the carpet shows Indo-Scythians or Indo-Parthians.

Divine mushroom

To the left of the altar is the king (priest), who is holding a mushroom over the fire. Opposite him is a warrior in a jacket with a “tail” and a belted quiver The embroidered plot develops further… We can see people standing absorbedly around the altar fire. The most prominent figure among them is the man on the left – probably, the king himself or a priest – dressed in a smart long embroidered kaftan gaping open at the bottom. He has a rarely expressive face, and his intent look is focused on the mushroom he is holding in both hands.

A priest with the Divine Mushroom in his hand... The question of what plant was used to prepare soma, or haoma – the drink of gods ancient Indians and Iranians imbibed has been debated for over a hundred years. Up to now, the plant whose sap was a permanent participant of the rituals, an offering to gods made by ancient Indians and Iranians, has not been identified. The hypotheses are plenty: from ephedra, cannabis, and opium poppy to oriental lotus (e.g., Abdullaev, 2009; McDonald, 2004; et al.). All researchers agree that ancient Indians and Iranians used for cult purposes a drink containing a psychoactive substance – it is only debatable what it was exactly and how it affected the people’s consciousness.

A scene from the Eleusinian Mysteries: Persephone taking a mushroom from Demeter. C. 4th c. BC

The translator and greatest authority on the Rig-Veda (RV) T. Ya. Yelizarenkova wrote: “Judging by the RV hymns, Soma was not only a stimulating but a hallucinating drink. It is difficult to be more particular not only because none of the candidates satisfies all the soma properties and matches the soma descriptions found in the hymns only partially but primarily because the language and style of the RV as an archaic cult monument reflecting the poetic features of ‘Indo-European poetic speech’ is a formidable obstacle to soma identification. The answer may be provided by archaeologists and their finds in north-western India, Afghanistan, and Pakistan (and not in te far-away Central Asia).”

This was written in 1999 – ten years before the outstanding find that testified that Indo-Scythians (Saka) and Indo-Parthians had used mushrooms for cult purposes.

The mushroom depicted on the Xiongnu carpet can belong to family Strophariaceae, according to Candidate of Biology I. A. Gorbunova (Laboratory of Inferior Plants, Central Siberian Botanical Garden, SB RAS, Novosibirsk). Its external appearance has similarities with species Psilocybe cubensis (Earle) Singer [= Stropharia cubensis Earle].

Many species of family Strophariaceae, especially genus Psilocybe, contain psilocybin, a unique psychoactive substance and a nervous system stimulator. The mushrooms having this substance play the leading role in T. McKenna’s psychedelic theory of evolution – one of the most original hypotheses of the origin of humans, their language, conscience, and culture.

A priest with the divinmushroom in his hand. Drawn from the carpet by Ye. Shumakova. The “divine mushroom” embroidered on the carpet resembles Psilocybe cubensis in its habit, shape of the cap, and stitches along the cap margin that look like radial folding or veil remnant. Dark inclusions on the stalk may depict the annulus that blackens because of falling spores. The mushrooms of genus Psilocybe, like many other species of family Strophariaceae, contain the psychoactive substance psilocybin. On the left is a king/priest with a mushroom in his hand. Drawing of the carpet by Ye. Shumakova. On the right is the fruit body of P. cubensis, grown on elephant dung (India). From: (Stamets, 1996). In the center is a diagram of P. cubensis fruit body. From: (Guzmán, 1983)

The Eleusinian Mysteries were the oldest religious festivities held in ancient Greece and dedicated to Demeter and her daughter Persephone, spouse to the underworld ruler Hades. The participants of the Mysteries ritually went through death and rebirth. It is known that the initiates were promised rewards in the afterlife. Those who had experienced the mystical death firmly believed that for them a new life would begin after death. “Happy is he who has seen this before sinking into the grave: he knows the end of life and he knows its god-given beginning.” (Pindar)

What particular rites made the initiates think of death with joy is not known. From of old, divulging the secret rituals was punishable by death. It is only known that the initiates were to live through and gain their own religious experience; there is evidence that the participants of the Mysteries had visions of images beyond thought. The prominent philosopher and Orientalist Ye. A. Torchinov puts it straightforwardly: “The Eleusis mystery is the mystery of psycho-technical experience of death and rebirth that purifies and integrates the myst psyche…” (1997, p. 145). To achieve this state, some hallucinogenic substances were used, maybe these contained in mushrooms

“Our remote ancestors discovered that some plants can suppress appetite, relieve pain, supply a sudden rush of energy and immunity towards pathogenic factors, as well as result in a synergy of cognitive powers… Alkaloids in plants, especially the hallucinogenic compounds such as psilocybin, dimethyltryptamine (DMT), and harmaline could be chemical factors in the protohuman diet that catalyzed the emergence of human self-reflection.” (McKenna, 1995).

It should be noted that toadstool (fly-agaric) has been nominated as a candidate for the plant equivalent of soma/haoma. This point of view was supported by the founder of the new science ethnomycology R. G. Wasson in his well-known book Soma: Divine Mushroom of Immortality(1968). However, mushrooms containing psilocybin prove to be much closer to the legendary “drink of immortality” in terms of their psychoactive properties.

Story told by the textile

Strewn all over the cloth are the depictions of bees and butterflies. Their presence can symbolize the Other World – the world of souls, the world of ancestors, where warriors get after they have tasted sacred mushrooms

To get to the root of the consecration unfolding before us, we should pay attention to such seemingly insignificant details as depictions of bees and butterflies strewn all over the cloth. These insects are the most ancient symbols of worship, and used to have the meaning very different from the present one.

The essence of these symbols of the living natural world, their mythological meaning can be understood through the words denoting them. A bee, for instance, in ancient times was identified with the Word (the first divine creation) and with the fire (soul). In this connection, the Old English beo (bee) can be related to the Indo-European *bhā- denoting, on the one hand, “to speak, word,” and on the other hand, “burn, fire.” In a similar manner, the Persian eng (bee) is related with the Aramaic ogi (soul) and Indo-European *og-en (fire) (Makovsky, 1996). The ancient mythology of many peoples is known to identify bees and people (in some aspects). The bee was Arthemid’s cult insect; Demeter and Persephone’s priestesses were called bees. A bee was the symbol of “honey” Indra, Vishnu, and Krishna. Atharvaveda compares spiritual pursuit with honey-making (Ivanov, Toporov, 1992). The antiseptic properties of honey made it and important means used by many peoples for preserving some foodstuffs, In Mexico, for example, honey has long been used to preserve mushrooms containing psilocybin.

The embroidered cloth covered the narrow space between the burial chamber walls and the coffin. On top of it was a layer of blue clay. Photo by Ye. Bogdanov

In Greek mythology, a butterfly personified Psyche. The Greek word “Psyche” means “soul” and “butterfly.” In fine arts, a soul was often depicted as a butterfly either flying out of a funeral fire or going to Hades (Losev, 1992). The meaning “soul” is often related with the meaning “fire, divine fire.” In Chinese culture, a butterfly is still an emblem of longevity. The insect’s life cycle – caterpillar, cocoon, butterfly – is perceived as a vivid example of metamorphoses leading ultimately to immortality or of a string of rebirths resulting in nirvana (Kravtsova, 2004).

M. V. Moroz, a fine art restorer with the Museum Studies Department of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography SB RAS, is engaged in near work: she is removing clay particles from fragments of the cloth

The butterflies and bees depicted on the background of the canvas may have symbolized the kingdom of souls – the Other World – the world of ancestors, where the warriors got to after having consumed sacred mushrooms.

…Now the puzzle fits together. The insects and the mushroom are closely connected and make the surrounding world miraculous. “We drank soma, we became immortal, we came to the light, we found gods.” (Rig-Veda. Mandalas 9—10. VIII, 48.3).

The time-worn cloth found on the floor covered with blue clay of the Xiongnu burial chamber and brought back to life by restorers has a long and complicated story. It was made someplace in Syria or Palestine, embroidered, probably, in north-western India and found in Mongolia.

The unique find is reviving thanks to restorers. From left to right: N. P. Sinitsina, a top grade fine art restorer (textiles and leather), head of the Leather Restoration Group with the Department of Non-Conventional Restoration Technologies at the Grabar All-Russian Art, Scientific and Restoration Center (Moscow); Ye. S. Sinitsina, a fine art restorer with the same department; and O. S. Popova, a fabric restorer with the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts (Moscow)

Finding it two thousand years later is a pure chance; its amazingly good condition is almost a miracle. How it made its way to the grave of a person it was not meant for will long, if not forever, remain a mystery.

And yet this is not the greatest enigma posed by the unique find. We were lucky to come across something completely new and out-of-the-ordinary. The border of the academic world was stepped across by unexpected evidence, tangible as the textile that has literally returned to us from the other world in order to continue the story about how a man was becoming Man.

References

Boyce М. Zoroastrians: Their religious beliefs and practices. Мoscow: Nauka, 1988.

Litvinsky B. A. Iranian and East-Hellenic temples of fire // The Hellenic temple of Oxus. Мoscow: Vostochnaya literatura RAN Publishers, 2000. V. 1.

Makovsky М. М. Language-myth-culture. Symbols of life and death. Мoscow: Vinogradov Institute of Russian language, 1996.

McDonald A. A botanical perspective on the identity of soma (nelumbo nucifera gaertn.) based on scriptural and iconographic records // Economic Botany 58 (suppl.). 2004. P. 147—173.

McKenna Т. Food of the Gods. Moscow: Transpersonal Institut Publishers, 1995.

Pugachenkova G. А. Khalchayan. Tashkent: FAN. 1966.

Schmidt-Colinet A., Stauffer A., Al-As Ad Kh. Die Textilien aus Palmyra. Verlag Philipp von Zabern. Mainz am Rhein. 2000.

Wasson R. G. Soma: Divine mushroom of immortality. New York, 1968.

Yadin Y. The finds from the Bar Kokhba period in the Cave of Letters. Jerusalem: The Israel exploration society, 1963.

Yelizarenkova T. Ya. On soma in Rig-Veda // Rig-Veda. Mandalas IX—X. Мoscow: Nauka, Literaturnyie pamiatniki, 1999. P. 323—353.

The photographs used in the publication are the courtesy of M. Vlasenko (Novosibirsk)